Willi Baumeister

Kopf (Collage zu Gefesselter Blick) / Head (Collage to Bound Look )1923 (image courtesy of staatsgalerie.de)

The Rabbit Hole

Viewing art is a lot like making new friends.

Each piece offers a new way to perceive a subject or circumstance. Each piece is an offering of insight and unique expression imbued with the flavor of the artist. As a viewer who is far from classically trained in art history or theory, I connect with styles, subjects, color choices, and meaning in the same way I do in encountering personalities and energy. When I go to a museum, my goal is to find a piece or an artist that speaks to me. I love perusing the rooms until something holds my attention, piquing a conversation or feeling within me.

This particular piece of writing was born out of an interaction with one painting that turned into a rabbit hole of research and getting to know an artist born in the city where I now reside.

Willi Baumeister, a Stuttgart native, was committed to not only creating art but also offering fellow artists a new way to frame their process of creation. From the time of his youth until his death, in his art studio where he was found with paintbrush in hand, acting as a channel of creation reigned paramount in his life. His theory was that art is a discovery by the artist from the universal unknown.

I’ve delineated some of the broad strokes of his life below, but truly, his life was so interesting. I admire his commitment to his craft as deeply as I admire his resilience in the face of the cultural climate in which he lived. I hope you enjoy getting to hear pieces of his story as much as I did.

I’d like to offer a special thank you to his daughter Felicitas Baumeister for managing his estate. Her curatorial endeavors allow all of us access to his collected body of work to this day. Without her, I might not have seen his works in either the Staatsgalerie or the Stuttgart Kunstmuseum.

I discovered Willi Baumeister’s work first in the Staatsgalerie, where many of his abstract and cubism style paintings reside near works by his dear friend, Oskar Schlemmer (another incredibly interesting artist. Please look up his costumes for the Triadic Ballet). I found another bank of his works in the Kunstmuseum Stuttgart. Both of these museums are located in Stuttgart, his birth place.

His works I first encountered in the Staatsgalerie came from his later years during which he was heavily focused on his abstract work. The pieces that first caught my eye were constructed with large swathes of black and white with punctuations of vivid color. Especially in Monturi mit Rot und Blau I (Monturi with Red and Blue I), the color placement, along with the fine lines leading the eye between color blocks offer a construction of well-balanced contradictions. The neutral color blocks are brought to equilibrium with sharp wiggles of vibrance. It brought to mind the experience of containing joy, not in a dampened way, but in a delighted shock of newness and exuberance at knowing something good is breaking up the monotony of daily life.

Monturi mit Rot und Blau I (Monturi with Red and Blue I) 1953

Upon further investigation into the title of the work, I was delighted to find Monturi is a word of Baumeister’s own invention and likely a reference to this specific art period in his practice. The lack of certainty around that assumption is equally as thrilling, implying it was a choice meant for his own cataloguing of creations. Thrilling because in a world where a viewer often must know the ins and outs of art history to obtain meaning, sometimes meaning is pure creation for creation’s sake.

Experience Informs Art

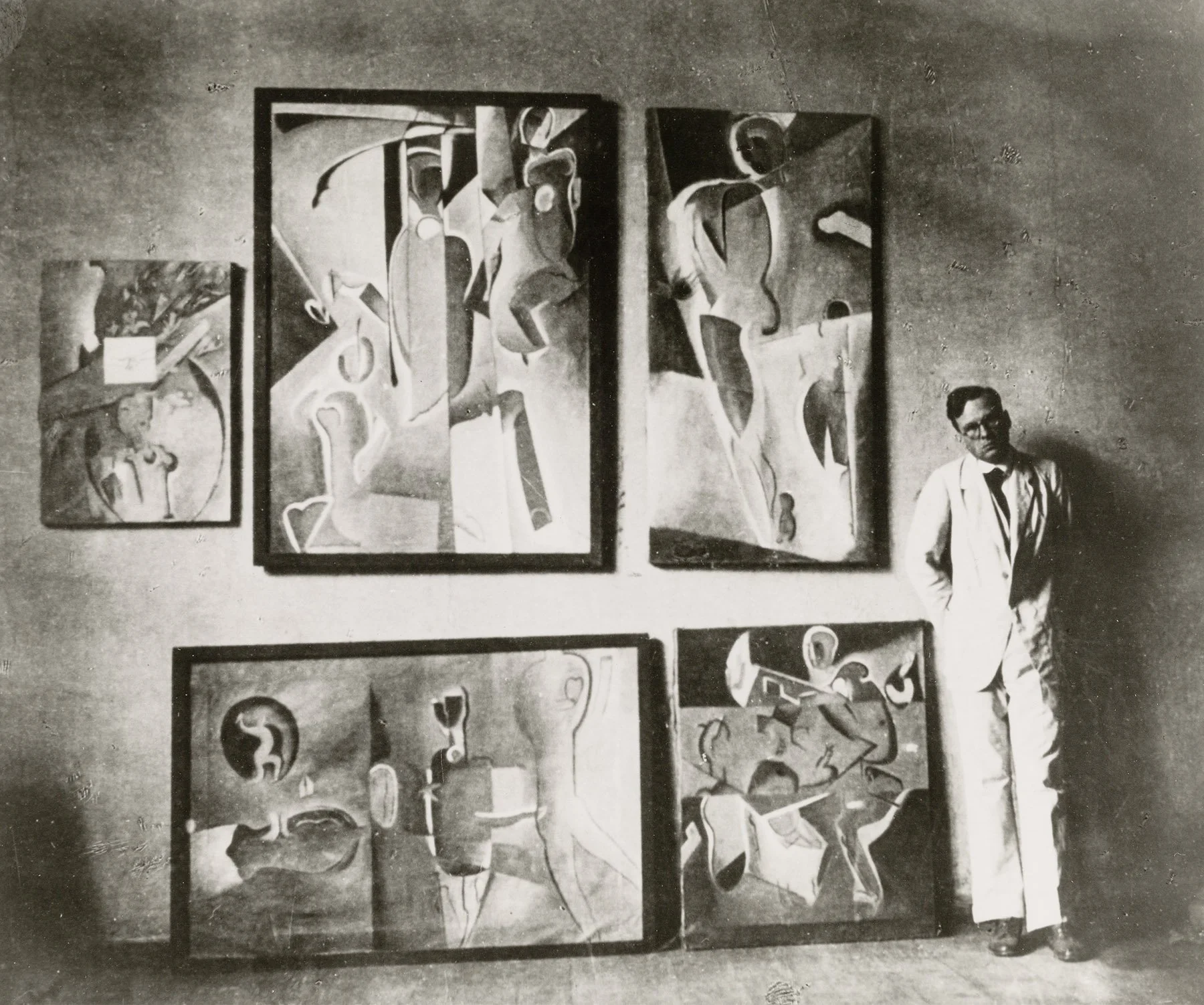

(image courtesy of willi-baumeister.org/)

Friedrich Wilhelm Baumeister’s life spanned from January 22, 1889 to August 31, 1955. His early artistic style was heavily influenced by prehistoric art. Much of his work can be divided into periods of prehistoric, cubism, and abstract styles. His later works, after World War II, leaned heavily abstract with influences from new objectivity and constructivism as he ventured further into his manuscript entitled “Das Unbekannte in der Kunst” (The Unknown in Art). The ideas presented in his manuscript spoke fondly of an artist’s spontaneous expression joining with nature’s creative power to culminate in art from an “unknown” origin, a source not easily explained by rational thought. He believed this was not only universally relevant but also an artist’s responsibility to humanity.

Baumeister experienced both World War I and World War II, but in vastly differing ways. He served four years in the German military during the first World War after being drafted in the summer of 1914. During his time in the military, he still managed to brush elbows and trade ideas with other prominent artists caught in the conflict despite the interruption to his early artistic career. After his time in the first World War, previous influences of prehistoric art and cubism became more muted in his art. He developed a new flavor in his personal style with his Mauerbilder works. These paintings have a highly textured effect due to the sand and putty Baumeister infused in his pigments.

Between the wars, Baumeister joined a Parisian artists’ group called Cercle et Carré (circle and square) in April 1930. The group was founded in late 1929 by Uruguayan artist Joaquín Torres-García and French writer Michel Seuphor with the goal of expanding the understanding of the constructivist art movement to embrace the inextricability of art and life, further exemplified by the group name symbolizing the totality of things both rational and sensuous. I particularly enjoyed reading his opinions on different art styles around this era. He preferred to steer clear of the subjectivity and emotion found in impressionism. He also found the morbid tone of surrealism to be repellant and abhorred its commitment to unconscious violent and destructive forces, yet he respected the movement’s manifestation of the unknown in contradiction to a sense of rationality found in other artistic styles.

Baumeister chose to resist the oppression of the Nazi regime in World War II. He evaded military service and continued to create art. His particular style of abstraction was branded “degenerate” art for its departure from the classical styles. He was let go from his position as professor from the Frankfurt Städel School by the Nationalist Socialists for this reason. Baumeister opted to gain employment at a varnish factory alongside his friend Oskar Schlemmer to earn a living helping with typography and commercial art. This job also effectively helped to conceal his true reason for having supplies that could tie him to practicing art in his home.

His commitment to art in spite of the Nazi regime earned him recognition within the art community. He not only gained status as a symbol of new beginnings for modern art after the war but also was granted a professorship at his alma mater, the newly reopened Stuttgart Art Academy in 1946. The following year, he published his manuscript urging other artists to contribute their particular brand of unknown to the visual repertoire of the art world. In his manuscript, The Unknown in Art, he discusses the impact of color, light, bias, style, composition, form, style, tension, and so many other things that impact the viewing and seeing of art. His analysis is thorough from movements to styles.

“Art had crossed the path from dependence to independence, from the com-

mission to self-responsibility. The sovereign, independent artist receives

his commission from himself, from his center, in which “everything is pos-

sible” again and again . . .” — Willi Baumeister

Possibilities in Art

Atelierbild (Studio Painting), 1925

The beauty in Baumeister’s desire to champion an artist’s own brand of bringing the unknown into the world is the offered artistic permission to create outside of the usual styles and categories of creation. As he argues in The Unknown in Art, “The special task of all painters is to discover new zones of seeing that were previously nonexistent, that were suspended in the unknown, and now can be grasped by their values and thus … formulate a universal syntax that [makes] the unknown—such as the imaginable, invisible, unconscious, or unfathomable—visible.”

He believed there is value in an artist's ability to express themselves as a vessel for whatever comes through their tools in an abstract or realistic manner. Each style has merit, each option evokes a different emotion in the viewer.

Upon reading his ideals for artists, I can’t help but to imagine how liberating that must have been to read as a fellow artist, art student, or creator of any type during that time. How beautiful to be reminded that your brand of art, your “unknown” waiting to be breathed to life in your creations, is not only wanted but imperative to the conversation of art in the world after enduring all the oppression of the war.

Until next time,

Aja